← All Newsletters • • 12 min read

I rebuilt Cold War nuke effects tables for a novel (here's how)

Newsletter #1 – How It Works: Methods and Accuracy

When you load the Nuclear Scenario Simulator, you see circles, plumes, and numbers.

To make that happen it took a mash-up of Cold War reference books, manually digitized charts, population data from Oak Ridge, and a lot of javascript code. (by the way, I hate javascript)

This newsletter is a tour of how it actually works, and why I trust it enough to build a novel on top of it.

Why I built this thing

The simulator started as a private research tool.

I'm writing a survival technothriller about a near-future nuclear exchange. If a character decides to airburst a 100-kiloton weapon over Tampa at 600 meters, I need to know:

- How far does the 5 PSI blast wave go?

- Where does the fallout plume actually land, with a given wind?

- How many people are in those zones at 2 PM on a weekday?

Existing public tools are great for "one bomb on one city," but I needed:

- multiple detonations on a timeline,

- realistic fallout,

- population-based casualty estimates, and

- something I could share with experts for advice easily.

So I researched how simulators like this can be built, and then went back to the original sources for verification and to improve my own understanding.

Ground rule: primary sources only

Very early on I set one constraint:

Only use original declassified government sources.

Try to make the best tool of this sort to date. No "close enough" curves from random websites. Every equation and coefficient had to come from the people who actually ran and analyzed nuclear tests. (thank goodness we don't actually do nuclear tests anymore, may it ever be so)

The simulator's physics model is built mainly on four documents:

- Glasstone & Dolan (1977) – The Effects of Nuclear Weapons

- CEX-62.2 (1963) – Nuclear Bomb Effects Computer

- Miller (1963) – Fallout and Radiological Countermeasures

- OTA (1979) – The Effects of Nuclear War

All of them are mirrored on the site if you want to read what I read.

The red dots: digitizing blast curves by hand

Here's one of my favorite bits.

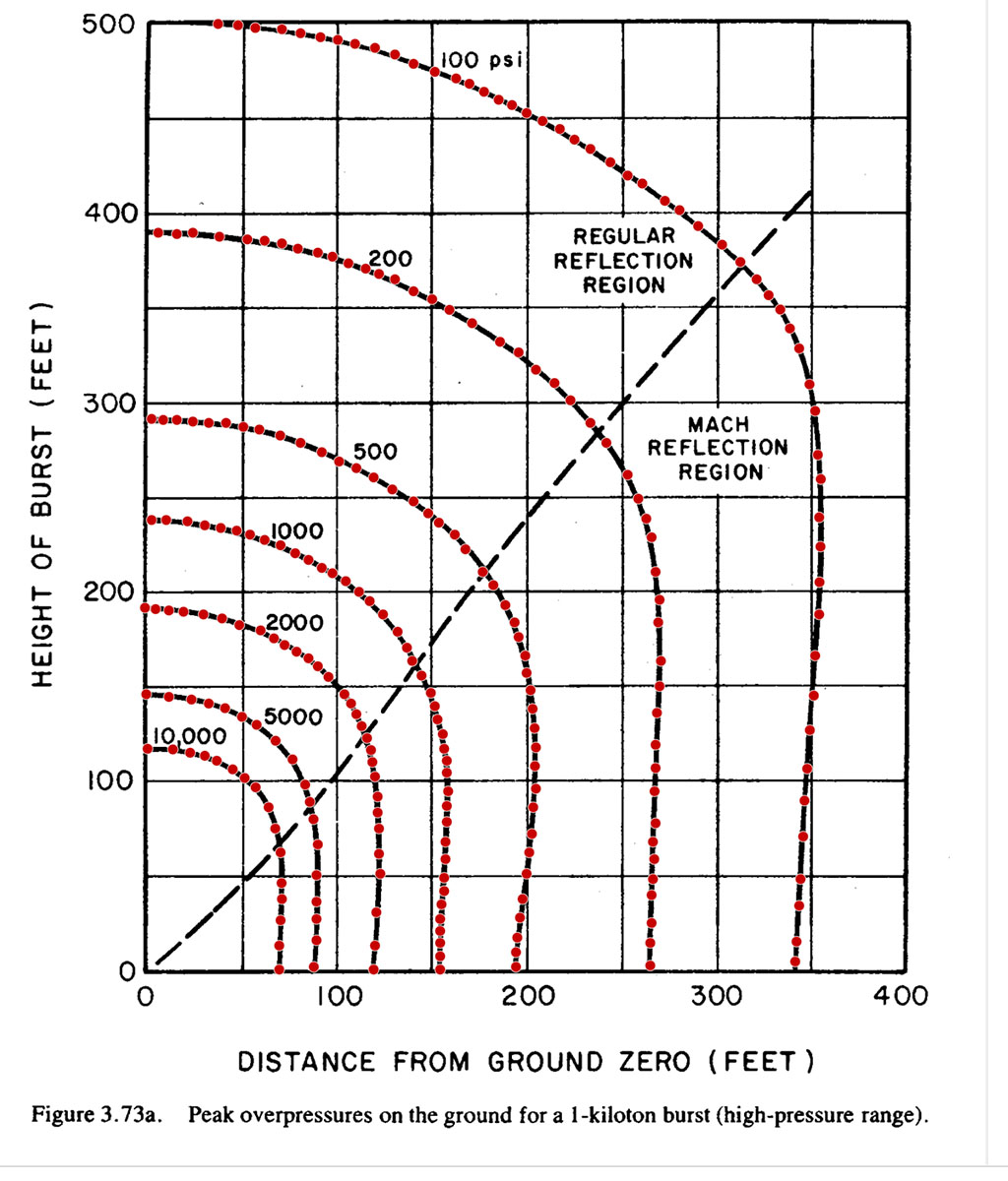

Glasstone & Dolan includes a set of famous charts (Figures 3.73a–c) that show how blast overpressure on the ground changes with height of burst for a 1-kiloton weapon. Think of them as contour maps: "at this height and distance, you get 5 PSI; at that one, 20 PSI," and so on.

To turn those squiggly lines into something a computer can use, I did this:

Each red dot in that image is one point I manually placed:

- Export the original figure at high resolution.

- Calibrate the axes in WebPlotDigitizer.

- Click along each pressure curve (1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000, 2000, 5000, 10,000 PSI), paying attention to inflection points.

- Export the data to CSV.

- Repeat until I had 582 points across 17 different pressure levels.

Those CSVs live in /source_docs/extracted_data/ on the site. The simulator uses them to interpolate blast radii for different yields and heights of burst.

Is that overkill? Probably. But now I can say: if you see a blast circle, it's tied back to an actual curve from the original 1977 book, not a guess.

Two big surprises

A lot of the math is exactly what you'd expect (if you're the sort who expects things from math at least): cube-root scaling laws, inverse squares, etc. A few things were more surprising.

1. Thermal burns go way farther than most online estimates

The CEX-62.2 report (the one behind the old "Nuclear Bomb Effects Computer" slide rule) has polynomial equations for burn thresholds.

When I implemented them, I found that the "real" thermal radii are roughly twice as large as the simplified web-friendly approximations.

For a 100-kiloton airburst:

- 3rd-degree burns: 4.56 km (vs ~2.31 km in old shortcuts)

- 2nd-degree: 6.30 km (vs 3.26 km)

- 1st-degree: 8.41 km (vs 4.45 km)

That means a lot of people who could have survived the blast will still receive fatal burns, especially if they're outdoors. It also raises questions for me about which structures will catch fire.

2. Real population data changes everything

Early in my work on this sim I kind of cheated to make the population stuff easy and assumed "5,000 people per km² everywhere." That seemed fine for a while, but it turned Montana into Manhattan.

So I switched to data from LandScan Global 2024, which estimates ambient population—where people actually are during an average day.

Some numbers:

- ~8.06 billion people represented

- ~45.9 million grid cells, ~1 km resolution

- Stored in a 3.8 GB SQLite database the sim queries live

When I re-ran the "Full Strategic Exchange" (3,266 detonations) with LandScan instead of fixed density, the casualty estimate dropped from 931 million to 555 million.

Not because I made it nicer, but because many strategic targets are in deliberately empty places: ICBM fields, radar sites, submarine bases. A flat population model just paints cities everywhere.

What the engine actually does

At a high level, each detonation goes through a few stages.

Blast

- Uses the cube-root scaling law (radius ∝ yield1/3)

- Adjusted for height of burst using those 582 Glasstone & Dolan points

- Produces zones like 20 PSI, 5 PSI, 1 PSI

- Validation check: for a 100-kt weapon at 600 m altitude, the computed radii match published values within ~0.1–2.7%

Fireball

- Uses Glasstone & Dolan's Y0.4 scaling for fireball radius

- Switches between surface-burst and airburst formulas based on height of burst

- For a 100-kt weapon, the fireball is on the order of 400–550 meters in radius

- Everything inside it is gone, but it's still smaller than the main blast zones, so it doesn't change casualty totals much.

Thermal

- Implements the CEX-62.2 polynomials for 1st/2nd/3rd-degree burn thresholds

- Produces burn rings that often extend well beyond the 5 PSI blast zone

- Assumes clear weather and line-of-sight (hills/buildings would reduce this in reality)

Fallout

- Uses the SFSS model from Miller (1963)

- Applies the wind-speed scaling Glasstone & Dolan specify (tables assume 15 mph; distances are adjusted up or down)

- Computes a 2D dose field with the classic cigar-shaped plume

- Applies the t-1.2 decay rule: dose rates drop to ~10% after 7 hours and ~1% after 49 hours

Right now fallout is visual only; it doesn't feed into casualty numbers yet. That will likely come later, once I'm confident about the behavioral assumptions.

Casualties

Casualty estimation happens in concentric rings:

- Blast zones first (200+ PSI, 20 PSI, 5 PSI, 1 PSI)

- Thermal zones outside those blast zones

- Radiation zones outside both

Each ring has a fatality fraction derived from the OTA Effects of Nuclear War report (which in turn draws on Hiroshima/Nagasaki data, test observations, building failure modes, etc.). To avoid double-counting, people are only counted in their worst zone.

A couple of sanity checks:

- A 100-kt airburst over Manhattan yields ~4.24 million casualties, which is grim but plausible once you include parts of Brooklyn, Queens, and New Jersey in the footprint.

- The same weapon over Death Valley yields 245 casualties. The ratio (~17,300×) is exactly the kind of Manhattan-vs-desert contrast you'd expect if your population data works.

What it doesn't model (yet)

A non-exhaustive list of things I don't simulate:

- Terrain and buildings (everything is flat and outdoors)

- Weather beyond "clear day"

- Shelter behavior (basements, interior rooms, etc.)

- Medical response capacity

- Fallout casualties over days/weeks

- Indirect deaths from infrastructure collapse, famine, disease

- Time-of-day population shifts

- EMP effects

For the novel, I still have to think about those. For a public simulator, I'd rather be honest and say "this is one physics-based datapoint, not an oracle."

How this ties back to the book

All of this work exists because I'm trying to write a story that doesn't cheat.

When a character in the novel looks at a map and says,

"That mushroom cloud has to be all that's left of MacDill Air Force base. Definitely a ground burst to rule out rebuilding. With the 25 mph wind out of the west we're going to be hit with 100 rad per hour when that fallout reaches us. That's severe radiation sickness for anyone not really well sheltered."

I want that line to be grounded in the same math you see in the simulator.

In return, I'm making the tool public because nuclear literacy matters. You don't have to agree with my assumptions, but you should be able to see what they imply.

If you're curious, you can:

- Load one of the preset scenarios

- Build your own

- Save a URL and send it to a friend with "look what happens if…" attached

And if you spot something that doesn't look right—or you work in a relevant field and want to help me make this better—I'd genuinely like to hear from you. Just hit reply, or email newsletter@dylanmalone.com.

Thanks for reading,

Dylan

P.S. Next time I'll talk more about the novel itself: the nuclear exchange, why Florida, and what it means to be the "knowledge broker" in a neighborhood where everything broke except the people who know how things work.